Books known only by title: a widespread but unexplored phenomenon

In Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone from 1997, JK Rowling refers by name to Harry’s textbooks at Hogwart’s. These references piqued the interest of fans, who were curious about the books – which did not exist outside this literary frame.

Following massive pressure from her fans, JK Rowling wrote the textbooks Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, Quidditch through the Ages, and The Tales of Beedle the Bard in 2001. Until then, they had been books known only by title.

‘In the same manner, first millennium religious texts contain several references to books that we only know the titles of’, says Liv Ingeborg Lied, a Professor of the Study of Religions at the Norwegian School of Theology, Religion and Society.

Liv Ingeborg Lied and Professor of Theology Marianne Bjelland Kartzow are leading the CAS project Books Known Only by Title: Exploring the Gendered Structures of the First Millennium Imagined Library.

‘Makes sense in a manuscript culture’

The international research group wants to understand conceptions of literatures and libraries in ancient cultures, when most people did not have access to many physical books. Some books they would handle and read, but others they knew only by reference or from hearing them recited in for instance church.

‘When we talk about the first millennium, it is really important to remember that this is a manuscript culture. If you wanted to distribute a text, you had to write it by hand’, Kartzow explains.

Books known only by title represent a widespread phenomenon that is more or less unexplored, Lied says.

‘Books known only by title tend to appear in literary texts and book lists from the Middle Ages, and sometimes as annotations in manuscripts. That is the material we explore.’

‘Among the many books we come across are the Book of Lamech, the Book of Zoroaster, the Hymnal of the Daughters of Job, the Gospel of Matthias and the History of King Herod.’

Some books known only by title surely existed, but were lost. ‘Then you have books first known only by title that people added contents to later, sort of like the Harry Potter example’, Lied says. Other cases are less clear-cut.

How do you know whether a book did or did not actually exist?

‘We don’t always know that’, Kartzow says. ‘We start with what we can actually know: since it is mentioned by title, at the very least, this book was known by name. Traditionally, our research tradition has said that these books probably existed, but were lost, but we ask: how do you know that? What if they are just rhetorical constructs?’

Lied explains that the scholars want to get closer to what a library entailed at the time. ‘It would be stocked with material books, and books that were only imagined. This makes sense in a manuscript culture.’

Since the material is so vast, the project leaders have limited their research to Christian, Jewish and Muslim sources. They describe what they do as “detective work”.

‘That is why it is so brilliant to be here. We do not know all the languages’, Kartzow says, although she and Lied impressively read Hebrew, Syriac, Greek, and Latin. ‘In our team, there is competence in different languages. Suddenly we hear about a source in Coptic that we didn’t know, and we add it to the list.’

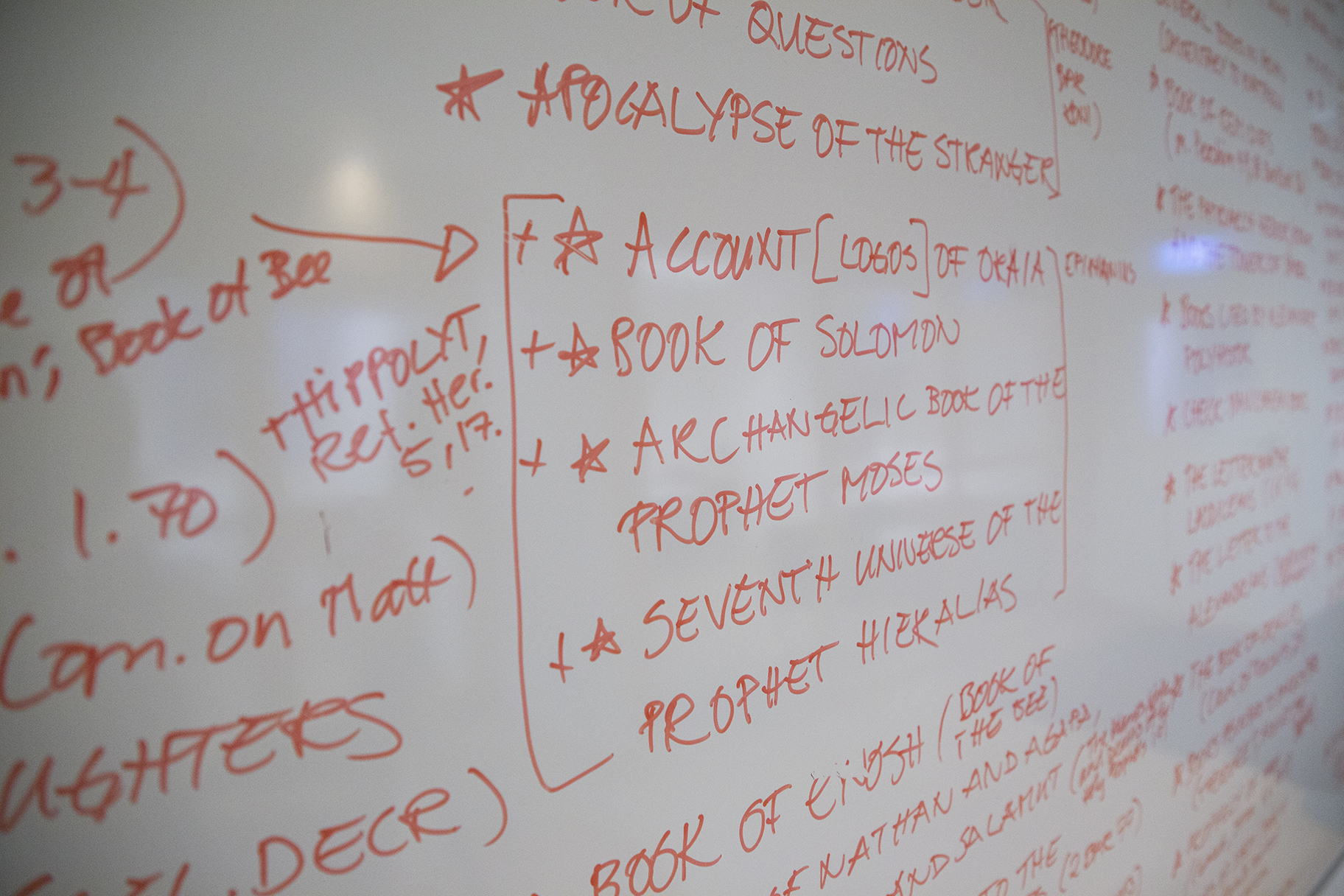

Their list is already long, and the whiteboard at CAS is packed with books known only by title. The plan is to make it into a database.

A break with traditional gender patterns

Before coming to CAS, the project leaders found out that several of these books known only by title are ascribed female figures.

‘They have been more or less overlooked by academics’, Lied says

This is something they will dig deeper into the rest of the year, but they already discovered that texts referring to books ascribed female figures have a tendency to break with the traditional story of knowledge transfer.

Typically, a story of knowledge transfer would be about a father transferring divine knowledge to his son, they explain. These stories often mention books, and many of these are known only by title.

In some texts, however, characters that are not fathers and sons, but slaves, women, daughters, sisters, and wives appear. Several of these books are ascribed to female figures such as Eve, the daughters of Adam, and the mysterious figure of Noriah.

Lied gives an example: ‘In the Testament of Job 46-51, the daughters of Job receive divine knowledge directly from a divine source, channel it and write a hymn book. This hymnal is a fictitious book, known only by title.’

The description of the daughters’ inheritance from their father on his deathbed is a radically different way of conveying knowledge, Lied argues. ‘The transmission process breaks with male lineage and the source of knowledge is not tradition passed down, but rather a hymnal containing “the magnificent things of God”.’

Knowledge can also be bad, illicit and dangerous, though, such as the knowledge that Noriah, the wife of Noah, received from higher powers. The book ascribed to Noriah is seen as heresy by the Christian writer Epiphanius of Salamis.

‘We want to use gender as a lens to highlight books known only by title ascribed to female characters, because no one has done that before’, Kartzow says, and adds that they also want to look at the general gendered structures in the ascription of books to ancient figures.

They also look critically at masculinity and authority when exploring these bodiless titles, and they find that male characters ascribed books known only by title are equally interesting vessels of the traditional gender stereotypes of the time.

‘Some of the figures on the list are male, but on some occasions their gender is not intact somehow’, Kartzow says, and explains that according to “ancient standards” a slave was not a proper man, because his body was owned.

Corona: from drawback to new possibilities

After a two yearlong planning period, Lied and Kartzow were ready to focusing on something unexplored over a whole year. Lied was a fellow at CAS 13 years ago, and had wanted to return.

Corona must have been a drawback. How are you solving it?

‘It is of course sad, but we choose to focus on the other narrative’, Kartzow says. ‘We think differently about collaboration and to appreciate the few people who are actually here. We are lucky to have two international researchers here.’

They are constructing a way of collaborating for the future, and the current situation gives them experience: a large part of the joint work takes place on a digital platform. This actually enables scholars who were supposed to come to CAS for a couple of months to join the project for the whole year, if they wish to.

A grand conference in March was replaced with a webinar series that will run from November to June.

‘This actually allows us to reach out to a broader audience, and may give us extra output’, Lied concludes.

Do you want to learn more about this project? Watch the project's webinar series