Making “demise” a topic in religious studies

When Michael Stausberg and James Lewis wrote the abstract for the CAS project Demise of Religions back in 2016, they didn’t know that the UN three years later would declare a crisis for the world’s insects and species, and that there soon would be various grassroots initiatives fighting extinction and degradation of nature.

They also didn’t know the western world would see a rise in “white supremacy” groups, which again could make a project about demising religions contentious.

Lastly, they didn’t know that a former IS captured slave, Nadia Murad, from the religious minority Yezidi, would receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

‘All these things make our project more relevant than ever’, Stausberg says.

The “left-over” category

The CAS project The Demise of Religions looks at different religions and examines their demise, from ancient Egyptian, old Norse, and Mediterranean religions, to so-called new religious movements in Japan, and contemporary, endangered religions.

As the CAS year is coming to an end, we gathered three of the project’s fellows for a conversation about the topic.

‘Demise has always been treated as fairly banal. It hasn’t been the centre of research, but the “left over” category that has simply described that something happened, and then it ended’, Richard Lim, one of the CAS fellows on the project, says, and compares the demise category to an already built lego-set.

‘We try to take the pieces apart and build them up differently again. We make demise a topic’.

The project gathered scholars from religious studies, ancient history, anthropology, and sociology to explore why and how religions meet with demise. Criticising the winners’ perspective has been the recurrent approach in the different cases, with several fellows suggesting that the demise of religions is often triggered by the advent of a bigger, stronger, and better religion.

From Aum Shinrikyō to Manichaeism

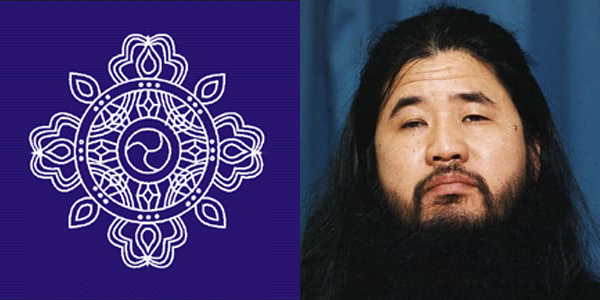

CAS fellow Erica Baffelli is an expert on contemporary religions in Japan, and works on a religious group called Aum Shinrikyō. Members from this group were behind the deadly sarin gas attack in Tokyo’s subway in 1995. Eighteen members were executed in 2018, and the organisation lost its name already in 1999.

Baffelli has interviewed some of the ex-members of the organisation.

‘In my opinion, Aum Shinrikyō was already dismantled in 1995. At the same time, they are pointed out as a security threat in Japan, which means that there is the perception that they are still there’.

‘The focus has been more on beginnings’.

Michael Stausberg comments that the questions the project is approaching are value-laden, and he is worried about the fact that their work easily becomes political.

‘For example, the idea that a religion, maybe Buddhism, is under threat, and that it needs protection, makes our topic in a way into a political issue. This is something I find myself worried about. It is almost difficult to say that Christianity is endangered when this is what certain on the radical right, white supremacy groups, now also claim. One wouldn’t really want to endorse their world view by our work’.

CAS fellow Richard Lim works on Manichaeism, a dualistic religion of conversion that was one of the most persecuted in its time. Against all odds, the religion spread across a geographical area that stretches from the Mediterranean and North Africa in the west, to China in the east. It is assumed to have existed in more than 1000 years, and the last evidence of its existence is from the temple Cao’an and texts from southern China (Quanzhou) during the Qing Dynasty between years 1600 and 1900.

‘However, we don’t know when these things were in use, which leads us to questions about what it means that a religion is alive’, Lim says.

Most people would think Manichaeism is dead, he tells.

‘But many would also say it could come back any time, because Manichaeism is an idea and a form that has been revived in many places’.

Michael Stausberg has, on his part, worked on the case of the Yezidis, a religious minority in Iraq that was brutally persecuted by the terrorist organisation IS in 2014, and that is still under threat.

‘Is there an option of return for this group? That seems quite unlikely. For this religion to be sustainable in other settings, where they have resettled, it needs to change drastically, so they are facing a very big challenge’.

The project leader says that gathering scholars working in such different cases has been a fruitful exercise.

‘It seems like the researchers who work on the ancient religions have taken more theoretical inspiration from the contemporary group, than vice versa. The researchers in contemporary religions have developed more models and causal thinking whereas the modernists have looked more into long-term factors than before. This has been an interesting experience’.

There is naturally a difference between looking at a religion that has been experiencing demise over a century, and a new religion with a short life, Baffelli explains.

‘Of course, we have different methodologies. For example, while I have interviewed those remaining in the Aum Shinrikyō religion, this is obviously not possible in the case of Manichaeism. However, it has been interesting to ask and frame similar questions’.

Lim responds that he also found it fruitful to read the other fellows' work.

‘For Manichaeism, demise is often a matter of duration; you come to an end because there’s nothing else to talk about because the sources go silent’.

He has been influenced by the questions that Baffelli and other fellows have asked about what is ending.

‘From initially exploring Manichaeism from an institutional level, I now ask what demise has meant for the people.’

Stausberg describes his time at CAS as a “holistic” experience.

‘I have seen things that I didn’t really think of before the year started’, he says. ‘For example, I really got interested in the topic of the deliberate destruction of religions. The initial idea was to look at the processes of how religions fade out of existing, but several of us got more interested in processes in which religions dismantle from the inside’.

One example is CAS fellow Janne Arp-Neumann's work on ancient Egyptian religion. She argues that what has been interpreted as demolition of reliefs may be evidence of religious change (link to article in Norwegian).

They all describe the year as more like a merry-go-round than a train ride moving in a linear direction. The carousel is magical, however, because the fellows see new things every time it turns.

‘For research grants, the goal is often a planned publication in a specific format. At CAS, the ride on the merry-go-round is sort of the goal itself. Most of us start out with an idea, let it spin, and pick up new ideas and input, or change seat from the horse to the pumpkin’, Baffelli says.

Having spent time with scholars from the other CAS projects has been refreshing, Lim adds.

‘The last time I had conversations with mathematicians was in Graduate school. The social environment at CAS is great. It is an intellectually stimulating place.’

Series of spin-off projects

The CAS year is coming to an end, and Stausberg is going back to his home institution, the University of Bergen.

‘Originally, I thought this would be a one-year thing. That turned out to not be the case, and I have new questions I take home with me and that will keep me busy for quite some years’. He gratefully acknowledges the new CAS Alumni fellowship that will enable him to develop some new angles in the future.

The project members have several book projects that are developing.

‘I think we all have material that we will continue developing for the next few years, that came out from this project. There will be a series of spin off projects’, Baffelli adds.