How Nordic societies weathered the last climate crisis

What can a humble potato or a ball of “witches’ yarn” tell us about climate adaptation centuries ago? And what can it teach us about our own climate responses today?

The potato, once viewed with suspicion as "animal fodder" by 18th-century Nordic communities, represents just one of many resources our ancestors utilised to cope with changing climate conditions during the Little Ice Age.

These stories of climate adaptation are brought to light through the NORLIA project, a collaboration between the University of Oslo and Klimahuset, and currently one of three CAS Research Grant projects for 2024/2025.

The project team is preparing to share some of these narratives in a new exhibition opening at Klimahuset in March. To learn more about the project and the upcoming exhibition, we spoke with PI Dominik Collet and Postdoctoral Fellow Ingar Mørkestøl Gundersen, both from the University of Oslo.

What is the Nordic Little Ice Age?

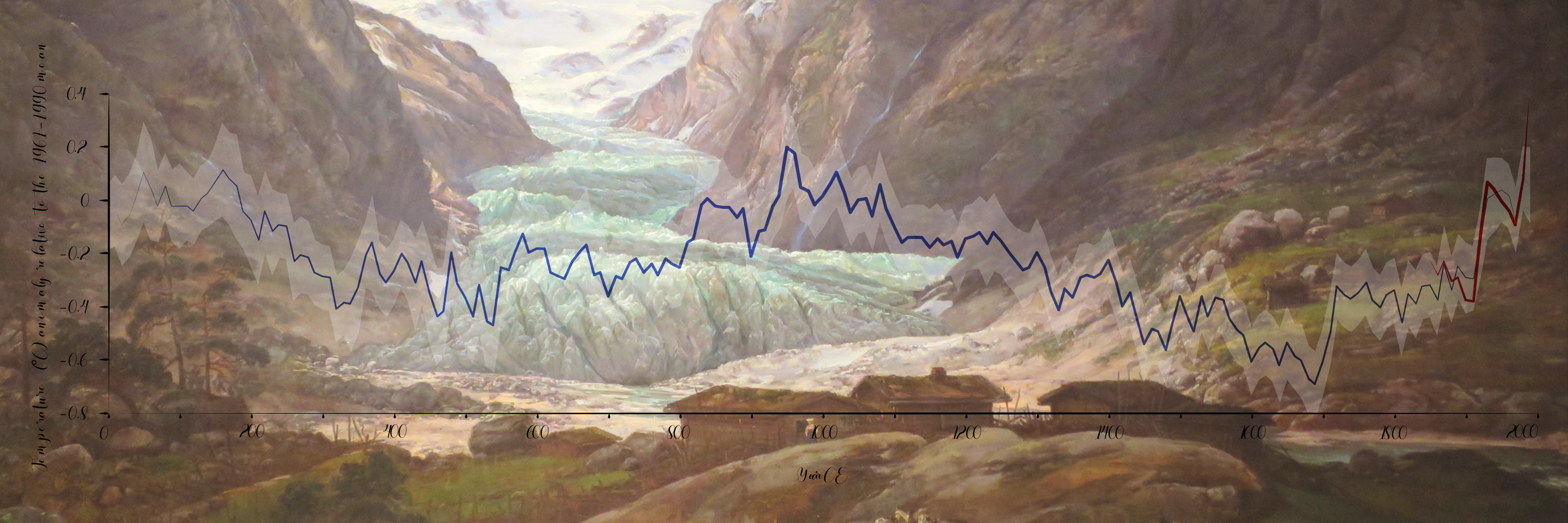

The Little Ice Age, spanning from 1300 to 1900, brought an average temperature drop of 1.5 degrees Celsius to the Nordic region – a shift remarkably similar in magnitude to today's warming, though opposite in direction. This parallel makes it a fascinating case for understanding how societies adapt to climate change. However, studying historical climate events effectively requires navigating the complexities of different academic approaches.

"Climate is a completely universal thing, right? It affects everything on the planet. But our science system is not universal. It is split into very fragmented and highly specialised disciplines," observes Dominik. He and Ingar note that academic disciplines often work in isolation, using the same words to mean different things – "collapse," for instance, means something quite different to a climatologist than to a historian.

The NORLIA project addresses this fragmentation by integrating climatological and historical perspectives through a 'socionatural' approach. By bringing scientists and historians together from day one, the project examines how natural and social changes intertwine. This interdisciplinary collaboration is needed for understanding climate history effectively and using historical climate responses to inform current debates and policies.

Learning from the past

While at CAS the project has focused on particularly extreme anomalies during the Little Ice Age, such as the 1740s, 1770s, and 1780s, revealing how societies coped with climate-related challenges through both institutional changes and grassroots movements. These historical examples suggest that today's climate solutions might benefit from a similarly diverse approach, rather than relying solely on technological fixes.

"What we can actually see is that they had a fairly broad range of responses, sometimes broader than what we are discussing today," Dominik notes. "We are very much focusing or hoping that there might be one technology that saves us, and these people didn't have this at their disposal."

Instead, historical communities adapted through a variety of means, from changing food habits to reorganising resource distribution systems. Some changes were small and immediate, while others – like questioning political arrangements and seeking self-governance – took generations to unfold.

"The current discussion is very technical," Dominik elaborates. "It's often about degree changes, gigatons, CO2 sequestration.” With the upcoming exhibition the team hopes to shed more light on past climate changes and their “lived” societal impacts, contrasting historical responses with current technical discussions on climate change, and bringing in the human experience as a narrative.

From raw data to human experiences – protests, potatoes and scapegoats.

The need to make the content both accessible and engaging for diverse audiences required careful consideration of storytelling approaches. "We did workshops where everybody was bringing an object connected to climate and telling a story about it, just to figure out what would work in an exhibition format", Dominik explains. Through these sessions, the team discovered ways to make the Little Ice Age's impacts resonate with modern audiences, transforming abstract historical data into relatable human experiences that visitors could connect with.

The exhibition highlights the variety of responses through themed sections on food, protest, and community action. Modern debates about food sustainability echo historical conversations about new crops like potatoes, and today's climate protests have historical parallels in how communities organised to demand change during the Little Ice Age. The exhibition weaves together scientific data from tree rings and early weather observations with deeply personal historical accounts, including artifacts like what Dominik and Ingar describes as "witches' yarns that were used to blame a 17th-century woman for working weather magic."

"We want to show that there's always choices available," Dominik emphasizes. These choices range from individual decisions about food habits to larger structural changes in how societies organise resources and govern themselves. However, Ingar notes that it's equally important to examine the missteps of the past: "It's not just about focusing on choice itself and constructive solutions, but also the bad choices that people made." He points to examples of scapegoating during times of crisis: "Some people felt the need to find scapegoats for their misery. The witchcraft trials are part of this story, but so too are the proposals by 18th century intellectuals and academics to improve the climate through “technofixes”. Their plans for massive deforestation in Norway are reminiscent of today’s geoengineering projects. They fortunately never materialised on the intended scale, but could have had grave consequences, despite their positive intentions”.

While climate change may seem overwhelming, history shows that communities have faced similar challenges before – and found creative ways to adapt and survive. Dominik and Ingar hope that when visitors leave the exhibition, they carry with them not just historical knowledge, but a new perspective on climate adaptation. The most valuable lesson from the Little Ice Age isn't about specific solutions, but about the importance of embracing a diverse range of responses – from the personal to the political, from the practical to the structural.

In facing today's climate challenges, we might do well to remember that no single new technology or adaptation may be enough. Like our ancestors, we'll need to draw on all our creativity and resourcefulness to weather the changes ahead.

The Nordic Little Ice Age exhibition opens on 18 March at Klimahuset in Oslo.

You can read more about the exhibition here >