Arbitration, Humiliation, and Submission: Peacemaking in the Middle Ages

It’s a common trope in media inspired by medieval history: In the middle of a bloody clash between warring factions, two commanders face off in single combat. Who lives and who dies determines the outcome of conflict.

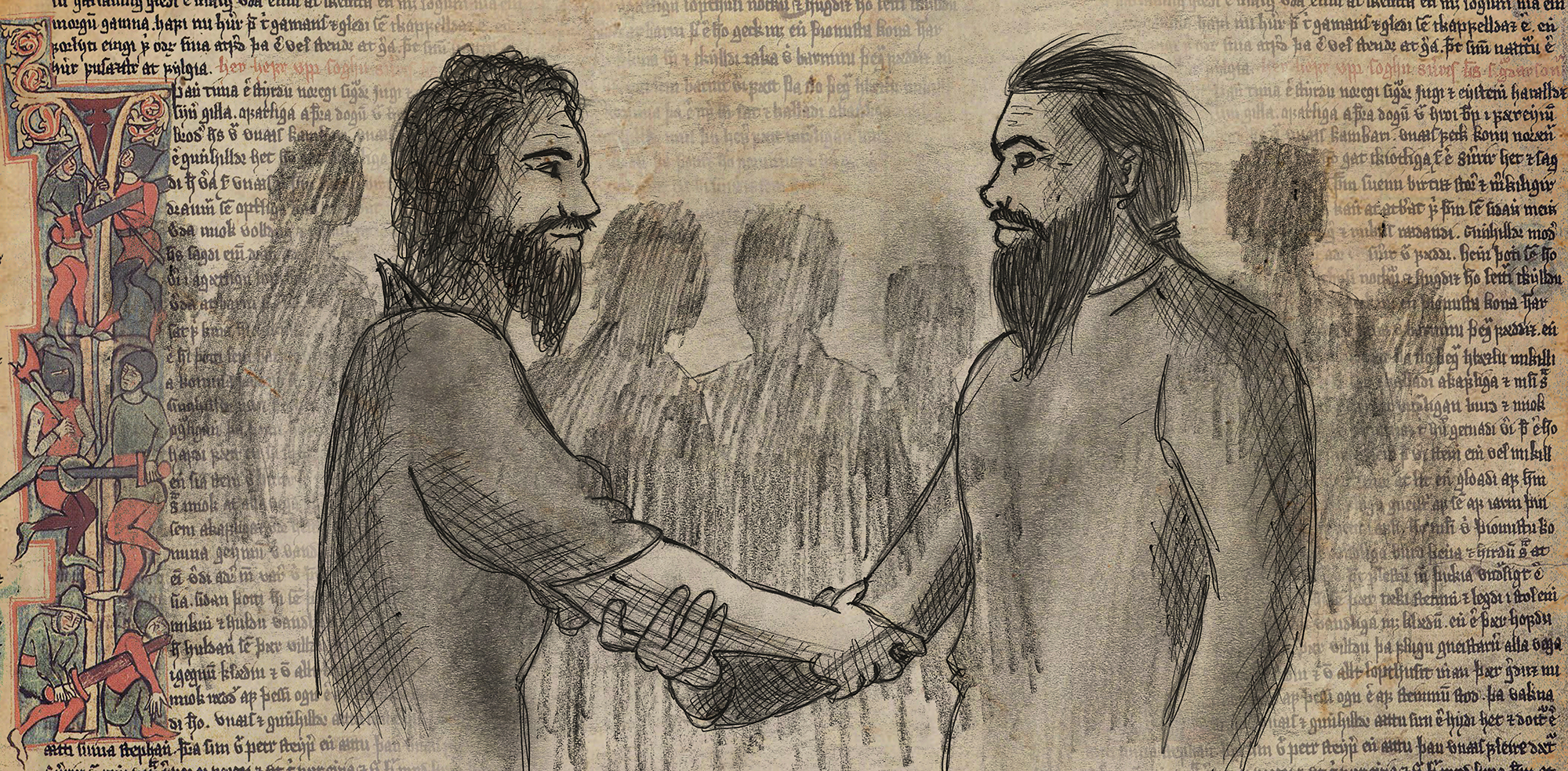

Historical records and chronicles from medieval Europe tell a more nuanced story, however. Conflicts during that age weren’t always resolved by one side soundly defeating the other. Instead, the path from war to peace often involved carefully choreographed, highly symbolic rituals of submission and transfers of money, land, and people.

Historians explored those peacemaking processes during a two-day conference last week at the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters. The conference, co-hosted by the Centre for Advanced Study (CAS) and the Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History at the University of Oslo (UiO), shed light on how medieval conflicts were resolved and violence was limited.

The conference, titled 'Peacemaking and the Restraint of Violence in Medieval Europe (1100-1300): Practices, Actors and Behaviour,' was organised as a part of The Nordic ‘Civil Wars’ in the High Middle Ages in a Comparative Perspective, one of three projects hosted at CAS during the 2017/18 academic year.

The 1074 uprising against Anno II, the archbishop of Cologne, is one such example. The uprising was short-lived -- some historical sources suggest the rebels were defeated in a matter of days. In order to atone for their insubordination, the rebels were forced to appear in public, barefoot and wearing robes.

But rituals of submission weren’t always a public spectacle. In Scotland, for example, submission was sometimes dealt with in a ‘very personal, private manner,’ said Iain MacInnes, a senior lecturer at the University of the Highlands and Islands in Scotland.

MacInnes pointed to an event referenced in the Scottish Annals from English Chroniclers, AD 500 to 1286, in which Malcolm III, King of Scots, is made aware of a plot hatched by one of his noblemen to assassinate him. Malcolm takes the nobleman hunting, and once the two are separated from the rest of the pack, turns to his would-be assassin and issues a challenge:

‘See, you and I are alone together, armed with similar weapons, borne on similar horses. There is no one to see, there is no one to hear, there is no one to bring support to either of us; if therefore you are able, if you dare, if you have the heart, fulfill what you have purposed, render to my foes what you have promised. If you think to slay me, when can you better, more securely, more freely, or in a more manly fashion? Have you prepared poison? But that is the way of weak women; who could not? Do you lie in wait by my bed? That can adulteresses also. Have you hidden a sword to strike secretly? That is the way of assassins, not of a knight; no one can doubt it. Act rather as a knight, act as a man, and fight man to man, that at least your treason may lack baseness, since it could not lack infidelity.’

The words strike the nobleman like a ‘heavy thunderbolt,’ and he throws himself at Malcolm’s feet to beg for forgiveness. Malcolm spares his life, in return for an oath of fealty and hostages, who ‘in fitting time returned to their friends, telling to no one what things they had done or said.’

While the history of medieval Scotland has been described as a ‘chronicle of carnage,’ MacInnes said, ‘evidence suggests the majority of those who rebelled were able to re-enter the Scottish political mainstream.’

Trust the Process

In the example of Malcolm and the nobleman, the king appealed to the traitor to ‘act rather as a knight.’ Such commonly agreed to moral codes helped defuse conflicts and save civilian lives across Europe during the Middle Ages, said Sean McGlynn, a lecturer at Plymouth University at Strode College in the United Kingdom.

McGlynn’s presentation focused on sieges, most of which didn’t end with the city being sacked, but rather were resolved through negotiation, he said.

During the Albigensian Crusade (also known as the Cathar Crusade) in southern France in the early 13th century, for example, the citizens of the town of Carcassonne were spared when they agreed to surrender. The citizens were not spared ridicule, however, as they were forced to leave Carcassonne in their underwear, exiting through a narrow gate where the crusaders could prevent them from smuggling anything out of the city, McGlynn said.

While traumatic, the fate that befell the citizens of Carcassonne pales in comparison to that of the town of Béziers, which did not heed the crusaders’ call to surrender. The crusaders took the city, burned it down, and killed as many as 20,000 men, women, and children, according to one record.

A respect for legal processes helped make Iceland what Jón Viðar Sigurðsson, professor of history at UiO, described as 'the most peaceful society in Europe' in the Middle Ages.

Sigurðsson is this year leading the project The Nordic 'Civil Wars' in the High Middle Ages in a Comparative Perspective along with his colleague at UiO, Hans Jacob Orning, professor of history.

Sigurðsson pointed to Iceland’s conflict resolution system as one of the main reasons behind the country’s relative peace compared to other regions in medieval Europe. In order to resolve their conflicts, opposing parties would bring their disputes to a court of arbitration, which could impose fines on a case-by-case basis.

Chieftains and bishops often served on the courts of arbitration, and -- due to the Iceland’s isolated location -- often knew the parties involved.

‘Arbitrators were under pressure -- not because they were friends or relatives of those involved, but because it was important … to make a ruling that both parties could accept and would not regard as an insult,’ Sigurðsson said. ‘Arbitrators knew that if they were involved in future cases where the roles were reversed, they risked getting the same punishment.’

Such an approach to conflict resolution in most cases resolved disputes quickly and to the satisfaction of the parties, Sigurðsson said.

In fact, so effective was Iceland’s arbitration process that even the question of whether the country should convert to Christianity was decided by a mediator. After a day’s contemplation, the mediator returned his verdict: Iceland would convert to Christianity, though pagans could still practice their faith in private. Both camps agreed to support the decision, averting a descent into civil war.

By Carl Fredrik Schou Straumsheim