Alumna of the Month: Liv Ingeborg Lied

The CAS project Books Known Only by Title: Exploring the Gendered Structures of First Millennium Imagined Libraries aimed to map and understand books known only by their title in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic literary sources from the first millennium. The project combined perspectives from Book History and Gender Studies to gain a deeper understanding of the cultural functions of books known only by title, particularly those associated with female figures.

The findings showed that books known only by title were widespread and served various purposes, including filling gaps in a chain of transmission and proving the antiquity of certain streams of knowledge. The project also revealed the limitations of past scholarship in ignoring these books and their cultural significance. During the research process, the pandemic posed challenges, but the project was adapted to include international fellows via Zoom and a webinar series. We talked to project leader Liv Ingeborg about her time at CAS.

Could you briefly explain what the CAS project Books Known Only by Title: Exploring the Gendered Structures of First Millennium Imagined Libraries, which you led with Marianne Bjelland Kartzow back in 2020/2021, was about?

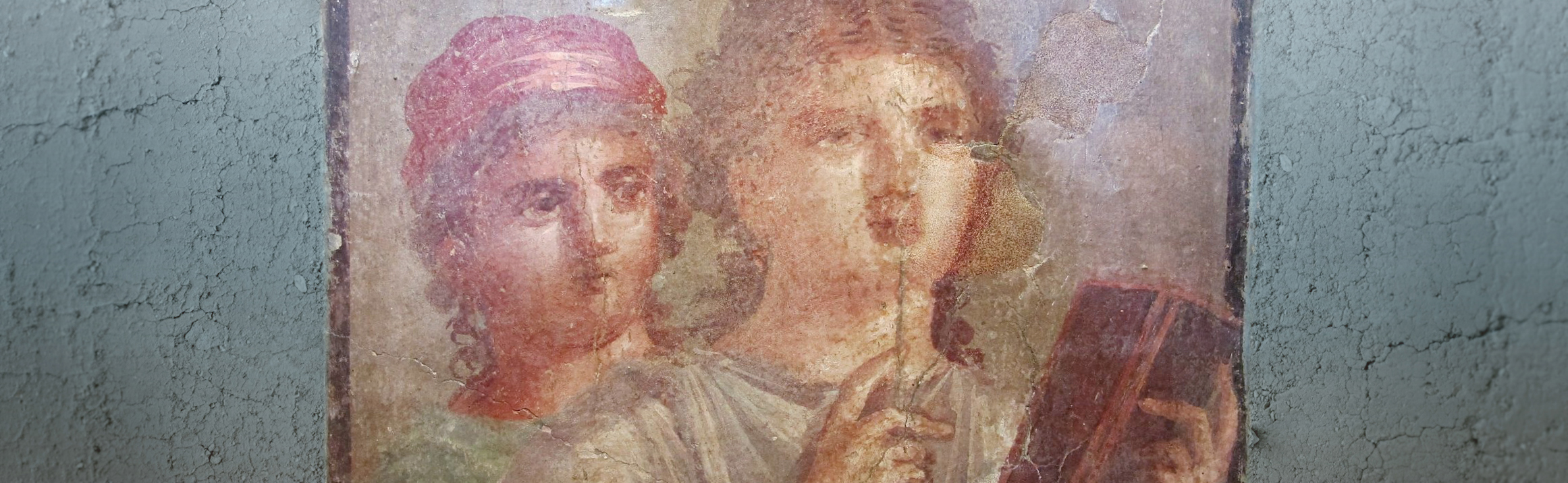

- As the title suggests, the aim of our project was to map, explore and try to understand the occurrences of books that are known to us only by their title in first millennium Jewish, Christian and Islamic literary sources and book lists. “Books known only by title” are named literary objects known only through other writings: they are embedded books, or books within books. These books manifest in their literary host but do not exist as extant texts in their own right. Books known only by title occur both in first millennium literature and beyond, but in scholarship they have rarely received any attention. When scholars have indeed commented on them, they have talked about them as “lost,” “fake,” or “fictitious” and hence not seen them as a worthy topic of research. We wanted to change this and to acknowledge that books may serve important functions as books that are being talked about and mentioned – even though they are themselves “textless.” We were particularly interested in books ascribed to female figures and the functions these books had in the literatures of the first millennium, since we assumed that associating books with female revelation, author or penmanship would serve particular types of meaning making.

Can you summarize the main findings of the research project and how they contribute to the understanding of books known only by title and their association with female figures from the biblical narrative?

- A first finding was that books known only by title were frequent! In August 2020, when we first arrived at CAS, we started writing down all the occurrences we were aware of at the time on the whiteboard in our common room. However, we very soon realized that the whiteboard would not contain the large mass of titles we were encountering – by far! Books known only by title were widespread indeed.

During our time at CAS, we isolated seven main functions that these books served in Jewish, Christian and Islamic literatures. Let me mention two of them: proving the antiquity of certain streams of knowledge and filling in gaps in a chain of transmission. For instance, several narratives from the first millennium claim that the knowledge they contain stem from the period before the flood. In order to argue their case, they note that the knowledge stem from books ascribed to antediluvian figures, such as Adam, Eve, Seth or Noah, and that the books survived the waters of the flood–sometimes in fanciful ways.

Other narratives stress that the knowledge has been transmitted in an unbroken chain via books handed down from fathers to sons. In order to ensure the reliability of the line of transmission, male figures that according to the biblical narrative had no books associated with them will have books ascribed to them in later writings. Abraham is one example of such a figure.

It is particularly interesting to look for books ascribed to female figures in these settings. When a male line of transmission is the commonplace and ideal line, bringing a daughter, mother or wife into the narrative changes the expectations. For instance, books ascribed to the daughters of Job bring extraordinary revelations into the world—knowledge not transmittable in the male line. The book ascribed to Noraia, the troublesome wife of Noah, contains all kinds of antediluvian wickedness. In other words, books known only by title and ascribed to female figures make it possible to imagine other kinds of knowledge—good or bad.

How does the project's approach of combining perspectives from Book History and Gender Studies enhance our understanding of first-millennium literary culture?

- Combining Book History and Gender Studies made us see how scholars of past generations have sometimes overlooked books ascribed to female figures and other times not grasped the literary functions of claimed female authorship, scribal activity and book transmission.

Furthermore, the book-historical perspective helped us think critically about the way scholars imagine the literature of the first millennium. For example, by ignoring books known only by title, scholarship has missed out on an entire shadow library. Just think about this: the imagined library of a learned person living in the first millennium would have contained more than books known as extant texts. It would also contain books that they would only have heard about and which were of unclear ontological status, as well as books that they probably knew were fictitious but that still could serve important cultural functions.

Did you face any challenges during the research process?

- We were at CAS during the pandemic in 2020/2021. It is obvious that this made for a very different year. In fact, all of our plans had to be changed—many of them several times. However, we decided to make the most out of it. We managed to get some of our international fellows into the country, and the others we met regularly via Zoom. From November through June, we also organized a webinar series where we invited international colleagues to join in. This made the small group present at CAS feel connected to a large community of peers online.

CAS’ mission is to further excellent, fundamental, curiosity-driven research. Why is fundamental research important, do you think?

- Let me start by saying that research that addresses societal challenges has much to commend it (I am a former member of the RCN’s SAMKUL steering board). Having said that, in my opinion, fundamental research is essential. There is no way around it. Fundamental research is what provides both the necessary overview and the equally important attention to detail that together builds expertise. Fundamental research brings out the complexity, grounds critique, builds new perspectives and prevents quick fixes.

In what way, if at all, did the year at CAS affect your research career?

- The year at CAS gave me the opportunity to delve into a new area of research. Many of the things I discovered while there will direct my research for years to come. My understanding of first millennium literature changed but perhaps more importantly, I see a growing need to challenge the academic imagination of the literatures of this period. I also discovered the surplus value of working closely in a team over time. This is something I would like to do again.

What are you currently working on?

- Right now, I have just started to work on a new project proposal. The project is related to the Books Known Only by Title project, but that is all I am willing to share about it right now.

Together with my co-editors, Esther Brownsmith and Marianne Bjelland Kartzow, I am also putting the final touches on a special issue and an edited volume that will summarize some of the main outcomes of our year at CAS.

What do you remember best from your stay at the Centre?

- The intense joy of arriving at CAS with the group in August 2020, knowing that we had a whole year of fun(damental) research in front of us!

What advice would you give to future CAS project leaders?

- I would choose a topic that I am really curious about. You will work on it intensively and for a long time. Also, I cochaired the project with Marianne Bjelland Kartzow and I would recommend future leaders to co-chair a group too. If Marianne is not available, then go for someone else who is equally great as she is!