‘The academics´ lack of engagement led to policy take-over of ethics debate’

As one of our measures to maintain high ethical standards and uphold fundamental principles for good practice, integrity, and ethics in research, CAS invited Vidar Enebakk to give a talk on research ethics.

Enebakk is the Director of the Norwegian National Research Ethics Committee for the Social Sciences and the Humanities (NESH), one of three national committees whose mission is to help publicly and privately initiated research follow ethical guidelines.

Research ethics: from hurting people to hurting research itself

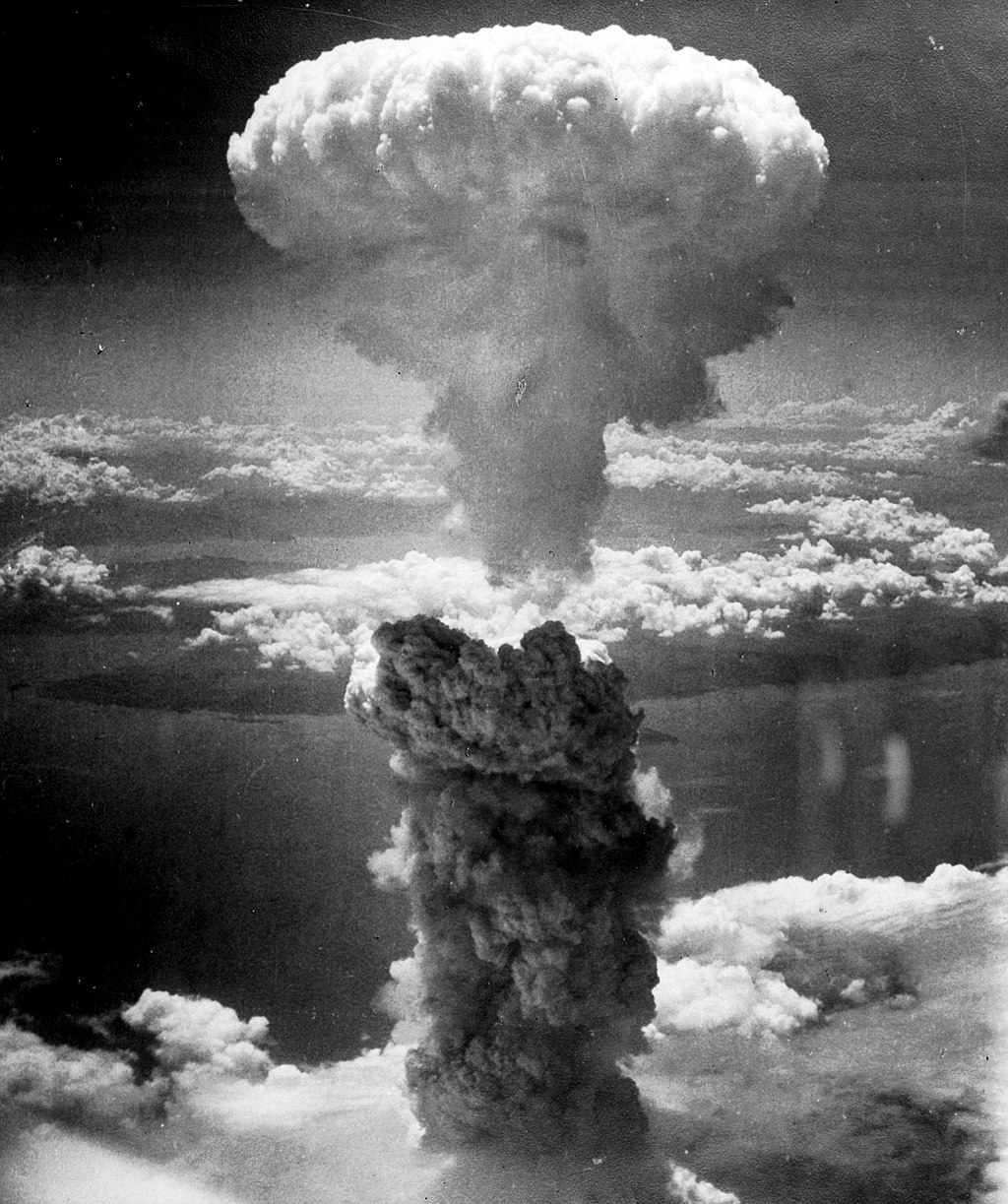

In what Enebakk called a “crash course in research ethics after World War 2”, he started out his seminar going through three modes, or discourses, that ‘led us where we are today’.

The appalling experiments on humans in the concentration camps during the war was one point of departure, but also debates on science and society, “Nazi science”,

The second phase in the 1970 came after the disclosure of the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiment, which was one of the triggers that led to the Belemont Report in 1978. A huge policy debate followed on how policy should regulate research, said Enebakk:

‘Do no harm, show respect, and make sure that people benefit from participation in research, was the new slogan for the time’.

Thirdly, more scandals were uncovered in the 1990s, this time with a new twist: falsification, fabrication, and plagiarism (FFP). These are narrow problems compared to what happened during World War 2, but with severe consequences:

'FFP has a different function. They don't hurt people or society directly, they hurt research itself. Science and the trust in research crumbles when you cheat or steal. That’s why it is policed so hard'.

'Lack of active engagement from researchers led to policy take-over'

Enebakk explained that with policy stepping in, academic self-regulation was partly replaced by laws governing research ethics.

In Norway, the infamous Sudbø scandal influenced the Norwegian Research Ethics Act of 2007. Ten years later, a revised version of the law was to “ensure that public and private research is conducted in accordance with recognized norms of research ethics”. Enebakk explains that in the revised law the institutions have increased responsibility. However, he is uncertain about the efficacy of the committees of misconduct, which every institutions must establish:

'What these committees should do is still unclear'.

As we can see from the historical development, policy and law replaced much of the academic debate on research ethics, Enebakk said:

'This has to do with the lack of articulation, codification, and active engagement with ethics in the broader academic community. If you do not do that actively and responsibly, policy and law will define the discourse about ethics, which is not necessarily best for research'.

Is research more unethical today?

In this interview, Vidar Enebakk and Scientific Director at CAS, Professor Camilla Serck-Hanssen, discuss research ethics.

What are the biggest challenges regarding research ethics today?

Enebakk:According to the recent RINO-report, there are two big, institutional problems: In a system perspective, the biggest problem is lack of education in research ethics. Secondly, people often do not know whom to contact if a problem arises.

The most common challenges are in grey areas, in which it is not clear what counts as a breach. Most people find for example the rules for co-authorship difficult.

The Norwegian National Research Ethics Committees also wants to draw attention to conflicts of interests in research. Many people report troubles either internally at the institutions, or in relation to financial sponsors etc.

The absence of conflict of interest in cooperation between a sponsor and a researcher is also problematic. Critical questions may be non-existent. That is also a major problem for the potential societal benefit of research. When it comes to conflict of interests, ethical problems are just as big when working with public bodies with a need for too much control, as with private institutions.

Serck-Hanssen:One recent example of a conflict is Katerini Storeng who experienced what she calls censorship when she did commissioned research for the British Department for International Development (DFID).

Enebakk:Much of the commissioned research is very good and professional. However, we are worried about other modes of knowledge-production (evaluations, analysis, design, and innovation) which lacks the standards of commissioned research. Is a ministry-commissioned report research? How can we trust the claims and conclusions in such a report or analysis? It is often unclear, both in policy formation and in presentation to the public, whether it is in fact research and to what extent it is independent.

Serck-Hanssen:

Another quite messy area is the use of research in politics, because there is so much cherry picking. On the one hand, researchers are not to blame when politicians refer to research arbitrarily or incorrectly, but then again the researchers’ motivation might be something else than to deliver research. She might well have a political aim.

Enebakk:Another murky field is publicly collected data. It is not always clear whether such data is collected for research or not. There is for instance a lot of research on our kids where consent, and the possibility to withdraw consent, is unclear.

Why are researchers fraudulent?

Enebakk:We need research to find out more about the reasons why researchers commit fraud. But many people point to changes in the research system. Especially young researchers are under a lot of pressure in order to gain funding and enhance their career.

What do we do if not only the apples are rotten, but the whole incentive system?

Through education and information, we have managed to raise the debate from the individual level to that of the local institution. Now we need to move beyond that, to the national and international system. What mechanisms and incentives make people do silly things and behave unethically? Is it advantageous that research institutions constantly depend on external funding?

Serck-Hanssen:Even at the universities, many researchers depend on external funding in order to carry out their research. Maybe it would be also ethically speaking more beneficial to incorporate means for research in the researchers’ positions.

Last year NIFU presented a report that showed how fraud in research was as widespread among researchers who published in the best scientific journals as in less prominent venues. The pressure to publish in them is tremendous- you get neither financial support nor a job without it.

Enebakk:The on-going global movement DORA challenges the system of research assessment based on quantitative indicators.

Serck-Hanssen:One need to work with research ethical questions continuously. A great researcher may end up in a work environment where it is acceptable to cheat a bit, and at one point, she might succumb to that culture.

Enebakk:As if it is OK to drive through a red traffic light if everyone does it. Education must incorporate ethical questions. This is even more important now that private sector stands for more than 50 percent of research. It is not enough to master theory and methods, researchers need to be good at ethics as well.

Is it more misconduct in research today?

Enebakk:No, not in the most serious FFP-domain, but we need to draw attention to the grey areas of questionable or unwanted practices. Not the least because many will work in the private sector. They must have high integrity, and they must know what research is.

Serck-Hanssen, what is CAS doing in order to take research ethical considerations?

Serck-Hanssen:CAS has become more aware of its role. We ask the project leaders to hand in a critical self-assessment of the ethical problems in their projects. This is new at CAS.

Additionally, we will have a seminar about research ethics every semester.

Together with the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, CAS has also set up a research ethics committee in order to handle possible cases of fraud.

Enebakk:CAS takes responsibility, and is an institution that has evaluated their responsibility and acted accordingly.

What ethical challenges may a CAS fellow meet?

Serck-Hanssen:I believe, there are no more challenges than other places, possibly even less. People at CAS have more time than most other researchers. It is of course up to each group leader how many publications she expects from the group. Nevertheless,

Enebakk:I hope that CAS fellows experience less pressure and more time; for instance time to read entire articles before citing them. This is one of the standards of good research practice that is frequently not met.

Research at a Centre for Advanced Study should be independent, critical, and anchored in academic freedom. I hope that if you push freedom, independence, and groundbreaking research, you also end up being aware of ethical questions. At CAS, researchers have the possibility to do groundbreaking research, and to explore and challenge ethical limits. I find that very exciting.